GUIGONE CAMUS

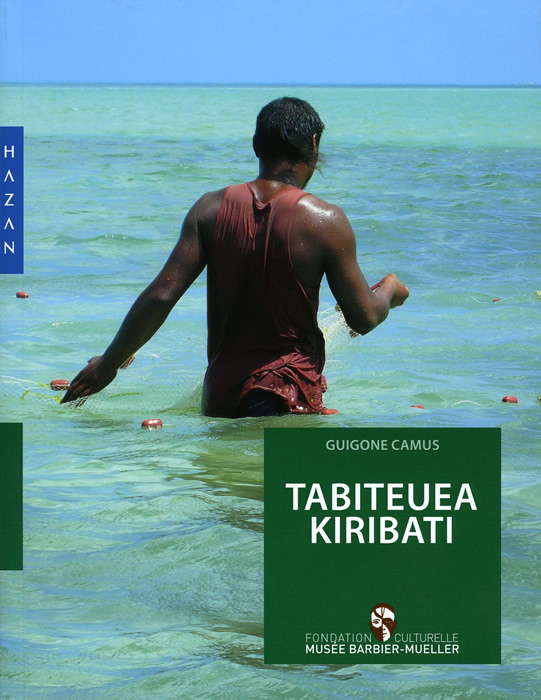

At the intersection of several disciplines, Guigone Camus’s ethnographic study of Tabiteua, an atoll part of the independent Republic of Kiribati, opens a window on the philosophical and spiritual depths, the poetry and the complexity with which the oral tradition and the social system mirror each other in a world of the spoken word, where ritual becomes the language of the community.

The ancient archipelago of the Gilbert Islands [1], situated within the confines of Eastern Micronesia and composed of coral atolls, is difficult to access, yet hosts a people who came to the island from Samoa over a millennium ago.

In addition to written documents (missionary, administrative and ethnographic archives), continuing to collect accounts of oral histories is imperative in conducting a historical and ethnographic study of the Gilbert Islands. The Gilbertese oral tradition, a privileged mode of communication, is a testament to a subtle and complex society. After all, what is more expressive, more revelatorythan a spoken story, and especially of a mythological one, in order to understand a society? What could possibly be more conclusive than the way in which a society speaks, recountsits own past?

To the Gilberts, the very existence of the gods is reduced to a simple manifestation: their presence is acknowledged in the material by the mere existence of rocks, without the further need for the construction of religious wooden sculptures or masks. Locations, on land or at sea, are considered to be traces of a deity’s passage on earth and are recognized as places of memory to be evoked in oral tradition.

Gilbertese Mythology

Even if, from a historical perspective, it is difficult to establish the chronology of the different voyages of the Gilbert Islands’ first settlers, it remains possible to identify the founding “epics” of the Gilbertese initial structure. hese stories set the scene for both the first settlers and the ancestors of the islands’ current inhabitants.

The important cosmogonical myth common to the majority of the islands recounts the way in which the powerful gods created the universe from an entity: “The Obscure and the Closed”. This myth lays down the foundation for the spatial and social organization of the society and is told through a series of dualisms, concentrating primarily on both the oppositions between the North and South as well as between the inferior and superior worlds. It puts the spotlight on the primordial deities linked to the natural worlds (sea, underworld – terrestrial, celestial worlds.)

Another series of myths, in line with these cosmogonical stories, concentrates on the creation of the mythical tree The Resting Place of the AncestorsTekaintikuaba, populated by deities residing in the base of its trunk, on its crown, as well as on its Eastern, Western, Southern and Northern branches. ter the gods in the trunk cut down the tree, the deities scattered, taking off either in canoes, “underwater canoes”, or “flying canoes”. They then settled down in the islands, though this step was not taken without comings-and-goings, nor without conflict or epic journeys, the lengthy process of which is extremely difficult to follow, from both toponymic and chronological standpoints.

Each god had the primary goal of building a big house, a gathering place for his descendants and for himself: the maneabaand to divide the land amongst himself and his descendants.

Mythology and Toponomy

The maneaba, always parallel to the sea, is a sober yet impressive construction. Up to fifteen such structures can be found on a single island (as is the case on the island of Tabiteuea, for example.) Wooden pillars (oka) support a roof which, in turn, rests on additional coral pillars (boua) that support its periphery. The subdivision of the interior, made possible by palm tree mats (inai) and pandanus leaves (roba), defines what are known as “seats”, or in Gilbertese: boti. These seats are spaces dedicated to the “clans” (kainga) descending from the great migrating ancestors. Over time, the space was re-divided in order to host new families, arriving in the region at a later time in either a pacific manner or following a conflict.

For its occupants, a seat (boti) determines a role within the community, a power which manifests itself in the maneabaduring large reunions by, for example, being the first to speak, the one to gather the people, the one to cut the fringes of the maneaba’s roof after reparation, as well as the one to distribute food according to ritualistic order. Additionally, each seat refers to power over the land which is observed outside of the maneaba. Indeed, for each family, belonging to one of this or that seat determines the parcels of land to which they may turn for habitation or cultivation (taro pits, palm tree plantations, and pandanus, fishing ponds, and parts of the lagoon).

In fact, mythology and toponomy are inseparable. All socio-political activities, such as land management [2], wars (alliances, conquests, appointment of factions to be opposed in war), alliances, etc., are based on myths and history relating to the island.

There is a surprising consistency between the different versions of the great myths of each island, which ethnologists such as the Father Sabatier (1886-1965), Sir Arthur Grimble (1888-1956), Henry Maude (1906-2006), Katharine Luomala (1907-1992) and currently Jean-Paul Latouche, were able to collect in the field. Meanwhile, they also reveal the extraordinary wealth of the myths in their various versions, on the scale of an atoll or even within a single maneaba. Through time, historical events have been integrated into the myths, and certain ancestors have become more prominent. Men have sometimes proven to be extraordinarily inventive in manipulating or even recreating myths for the benefit of their property or for their own prestige.

The Exemplary Case of the Tabiteuea Atoll, in the South of the Gilbert Islands

Tabiteuea atoll is a particularly interesting example in this respect. In fact, its creational myth is relatively independent from those of other villages such as Tarawa-Abaiang or Beru-Nikunau. Before the ancestors originating from the Tekaintikuabatree created their maneaba, the cosmogony mentions the creation of a sandbank in the Tabiteuea lagoon, a place named Takoronga, which would be at the origin of everything.

If Tabiteuea is an interesting example due to the particularity of its myths, it is equally interesting due to the atoll’s history. On two occasions, the island hosted violent clashes between Westerners and the islanders. In 1841, following the disappearance of one of its crewman, the men on the Peacock, a ship participating in the Exploring Expedition [3], the Panama, set fire to the village of Utiroa.

In 1880, Kapu and Nalimu, missionaries from the Hawaiian Evangelical Mission, encouraged their followers to exterminate the non-Christians of southern Tabiteuea. The consequent religious conflict climaxed in the bloody battle of Tewai, in the south.

Following research conducted in the London archives (SOAS) and the Honolulu archives (HMCS and HHS), I have attained much first-hand data on the history of the Tabiteuea. These findings will be illuminated by the testimonies I gathered during my field research.

The urgency of research

Conducting research in the Gilbert Islands is a real urgency, stemming from the environmental situation. In fact, the atolls and their assets are severely threatened by the rising seas predicted by 2050. In December 2009, Aata Maroieta, an inhabitant of Tebunginako on the island of Abaiang [4], testified on this topic in Le Monde.fr’s [5] online video for the Copenhagen Summit:

“We live in constant fear, imagining that one day, the Kiribati Islands will disappear. My greatest worry is of losing my identity along with I-kiribat and of losing my land on this island. It is my greatest fear. I don’t have much hope for the future if nothing is done. We have never heard of the problems that we face today. If the cause of all of this was natural then we would have already faced something similar in the past. It is only recently that we must face them. So, I believe developed countries are responsible.”

This problem also echoes the plea issued by the Federated States of Micronesia at the Majuro summit (Marshall Islands) on July 9, 2009, destined to alert the international community to the necessity of limiting greenhouse gas emissions.

Considering this danger, first, an ethnographic study on the island of Tabiteuea would represent the beginning of the enumaration of an ensemble of Gilbertese oral traditions. This study, thanks to the support of the Barbier-Mueller Foundation, will then emphasize the importance of the oral tradition, especially regarding the way the Gilbertese define their identity and culture.

L’Humanité Dimanche, 4-10 September 2014

NOTES

[1] The ancient Gilbert Islands, thus named in the 19th century by the Russian geographer Krusentern, are today members of the Republic of Kiribati. There are sixteen islands: Abaiang, Abemama, Aranuka, Arorae, Beru, Butaritari, Kuria, Makin, Maiana, Marakei, Nikunau, Nonouti, Onotoa, Tabiteuea, Tamana, Tarawa.

[2] Land was inherited either from the father or the mother.

[3] The Exploring Expedition was the most important American, scientific (collection of animal and vegetal specimen, hydrographic surveys, etc.) and diplomatic expedition of the 19th century, conducted between 1838 and 1841, by Capitan Charles Wilkes.

[4] In the north of the archipelago.

[5] http://www.lemonde.fr/le-rechauffement-climatique/visuel/2009/12/09/2009-2050-le-rechauffement-climatique-a-hauteur-d-homme_1278216_1270066.html