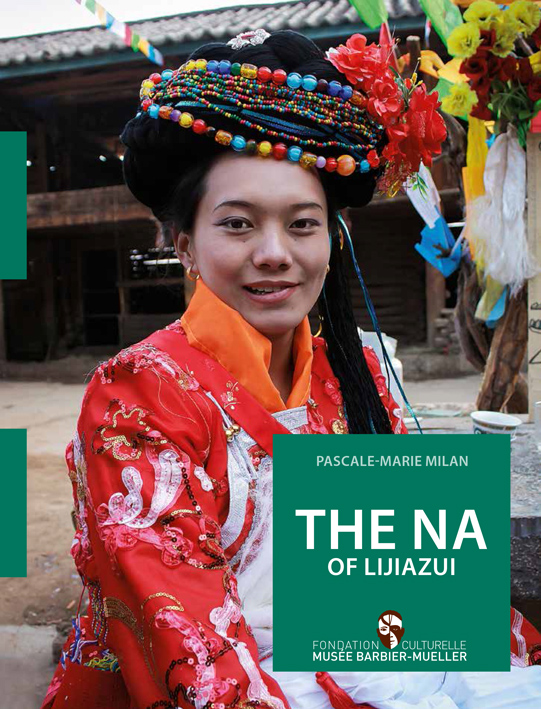

PASCALE-MARIE MILAN

In the cold mountains of Sichuan (Liangshan) in China, about fifty kilometres from the Lugu Lake region subjected to the glare of the media, the author conducted an up-close ethnographic study of the Na. More than two years of fieldwork allowed her privileged access to the underside of the social fabric.

Her immersion in the ordinary life of the Na and her participation in various everyday activities allowed her to shed the anthropological exoticism in which explanations of the group are generally couched. Songs, dances, myths, rites, and mutual aid and exchange all provide windows on to the emotional tenor and logic of the Na system of thought. They make possible an assessment of contextualized practices, based on the justifications the villagers give from within their historical, economic, political and ideological constraints.

PRESENTATION OF THE NA BY PASCALE-MARIE MILAN, THE AUTHOR’S BOOK

The Na live in territories in the foothills of the Himalayas, on the border of Sichuan and Yunnan provinces: Lugu Lake, the Yongning plain, the Liangshan mountains and the county of Ninglang. They are better known today by the name “Mosuo”, despite constituting a disparate group with respect to the semantic divisions of the historical ethnonyms (Nazé, Nari, Nahing, Naru). [1] Widely discussed by anthropologists because of their matrilineal kinship system and their matrilocal residence, they appear to be a special case in the ethnological landscape, since they do not marry and practice a type of free sexual union, called Séssé. [2] Their social organization into a matriclan confers on the Mosuo certain particularities no longer found among the neighbouring Naxi of Lijiang, such as the transmission of property and filiation through the women.

Na girls wearing wool-and-bead head coverings made by their elders. Photo Pascale-Marie Milan, 2013.

The Na in the literature

The history of the Na dates back to the most remote times of imperial China, via a long written tradition recorded in the Chinese administrative annals. Among other things, we know that the regions populated by the Na resulted from a migration of the Qinghai plateaux. Some say that the Na are mentioned for the first time in the annals under the Eastern Han Dynasty (Dong Han, 25–220), in narratives relating the superiority of the women and the matrilineal system in the region. [3] Others say that the first writings date to 225, with the appearance in the Chinese annals of the ethnonym Mo-sha to refer to the inhabitants of the Yanyuan region.[4] Traces of this people are also found under the Tang Dynasty (618–907). [5]. A few sources written by explorers or missionaries satirize them. [6] But the systematic study of the Na began only with the launch of a classification project in 1956, whose aim was to control minorities. For a long time, however, they had escaped the historical administrative control of imperial China, [7] because they lived in craggy and largely inaccessible territories. [8] Despite these sources, the history of the Na as they themselves experienced it is still veiled in obscurity, since there are no endogenous written sources. The Na are in fact a people without writing, whose oral history was transmitted for centuries through myth and song.

Considered a “primitive”, “uncivilized” and “exotic” population by the Chinese, they were granted the status of minzu, being officially categorized as Naxi in 1958, during the ethnic classification project.

Séssé

The majority of the Na practice Séssé, in which men visit nonconsanguineous women at night. A furtive activity, the Séssé for those who engage in it is a modality of noncontractual, nonobligatory and nonexclusive sexual life9] that belongs to the Na matrilineal kinship system, so much so that it anticipates both the principle and the foundation of the cultural values that give meaning to the life of the Mosuo. [10]. It is a historically dominant mode of identification “practised by all the Na”. [11]

The region of Lugu Lake, very exposed following the spectacular rise of tourism there, [12] is the principal focus of research on the group. Yet the Na are geographically dispersed. They also populate the Sichuan region of the Liangshan mountains, especially the Muli Autonomous Tibetan County in the hinterland of Lugu Lake. These Na, dispersed in mountain villages (the village of Lijiazui, for example, where I conducted my research), are officially categorized as Mongols. The Nazé of Lijiazui attribute various images to themselves. They claim, for example, to be the possessors of a certain “tradition”, unlike their Lugu Lake neighbours, who now call themselves Mosuo. Their rich oral literature is in danger of being lost, as a result of an ever-increasing Sinicization. Having become a minority in the region over the course of time, they face various pressures (economic, political, ecological and so on) resulting from different interactions and social reconfigurations.

Séssé, a historical practice and the nexus of Na society, [13] still remains at the root of what allows the Nazé to constitute a society and to define itself as a unique ethnic group. The practice is explained in a range of myths and songs that are being forgotten, given the strong tendency toward Sinicization and the Chinese state’s efforts to rewrite these works, which are sometimes judged indecent. [14] In view of that threat, it was urgent to collect this corpus through audiovisual media (recordings, videos, and so forth). It was also necessary to document and analyze the practice through observation, interviews, and photographs, but without engaging in the typical idealized caricature, as has occurred at Lugu Lake, where the tourist industry has largely used it to ensure local colour.

This practice is accompanied by rites of passage that needed to be brought to light, contextualized and situated. For example, the transition to adulthood, the birth of children and the end of sexual life are all markers in the lives of the Nazé of Guabieka. They have been documented and analyzed, inasmuch as they belong to social and symbolic life and allow for the ethnography of local customs.

Na children and their aunt. Photo Pascale-Marie Milan, 2013.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study, then, is to provide further data about the Na living out of the media spotlight of the Lugu Lake region, through the use of a preexisting body of literature centered primarily on the Na/Mosuo of Lugu Lake, in line with the anthropological studies of Eileen Walsh, Cai Hua, Chuan-Kang Shih and Christine Mathieu. Its purpose is to gain an understanding of the local interactions and structures that maintain the Nazé social fabric in a lasting manner.

NOTES

[1] These divisions are a result of the richness of the oral Na language (Michaud 2008).

[2] Cai 1997, Shih 2000, 2001, 2010.

[3] Cai 1997, p. 14. 14.

[4] Yanyuan is a town located east of Lugu Lake in Sichuan Province, in the heart of the Liangshan mountains, where Stevan Harrell conducted a number of studies. Mathieu 2003, p. xxi.

[5] McKhann 1995, p. 48; Shih 2010, p. 23. 23.

[6] Cordier 1908; Rock 1947.

[7] This statement needs to be put in perspective, given the complex relations between Naxi and Mosuo. Nevertheless, it seems that the Mosuo were less inclined toward Sinicization because of the inaccessibility of the Lugu Lake region, which even today is marked by climatic constraints (landslides, snow).

[8] Cai 1997, pp. 51-52; Mathieu 2003, p. 2. 2.

[9] Shih 2000, p. 697. 697.

[10] Shih, 2000, p. 701. 701.

[11] Cai Hua 1997, p. 143. 143.

[12] Walsh 2005.

[13] Shih 2000, p. 701. 701.

[14] Trebinjac 2008.